In the aftermath of an earthquake in Iskenderun, Turkey, a family is grappling with the structural integrity of their apartment building.

In the aftermath of an earthquake in Iskenderun, Turkey, a family is grappling with the structural integrity of their apartment building.

“The crack runs through the entire wall”

One year after the severe earthquake, hundreds of thousands of people in Turkey are still living in shelters – despite the authorities urging them to return to their dilapidated houses. “Nemo is still living in his first house,” says Bünyamin, as he throws some fish food crumbs into the small aquarium for his goldfish. The 9-year-old has been living with his family in a shelter for a year. He was able to save his beloved Nemo when the family hastily left their basement apartment during the earthquake on the night of February 6, 2023, which lasted for almost a minute.

Bünyamin lives with his older brother Hüseyn and their parents in a container village in the port city of Iskenderun in southern Turkey. However, the authorities now want them to move back to their old house, claiming that the damages are not severe.

This is a terrible thought for Bünyamin. He is afraid that there might be another earthquake and this time the house will collapse, just like many buildings did a year ago. “If we are in the basement, there is no chance of survival,” he says seriously. “The whole house will fall on us, that’s why staying here in the container is good for us.”

Erdogan opens new settlements

Bünyamin’s mother, Mehpare, shares her son’s concerns. For months, she has been writing to the authorities or trying to personally make them understand that she and her family cannot return to their old apartment anymore. “As soon as I enter the house, everything comes back. We went there a few times during the day to retrieve some belongings,” the petite woman explains. “We quickly went in and out. If they tell us now that we have to leave, I would rather set up a tent in the park than go back to the house.”

Still, about half a million people in the affected region are living in camps, just like Bünyamin’s family, either because they fear moving back into a house or because theirs was destroyed or severely damaged. Many people still rely on support, often organized through private donations.

Three days after the earthquake, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced his plans to rebuild the area within a year. Now, just before the anniversary, Erdogan is touring the region and inaugurating the first new settlements.

Should the historic city be demolished?

This includes Antakya, the city that was hit the hardest and still presents a devastating picture of destruction. According to government representatives, 20,000 apartments will be completed throughout the province, but a much larger number is needed. However, that alone is not enough, says Buse Ceren Gül, one of the architects involved in the reconstruction. “I think it will take ten years until there is a place that we can call Antakya again,” she suggests. She herself comes from the historic city, which was almost completely leveled.

But tearing down everything and building something new would erase the city’s history. “In Antakya, we had mosques, churches, synagogues, some on the same street,” Buse describes her hometown. It was a place where different people lived together. And that’s my main goal: to recreate this coexistence.”

Buse herself lost her grandmother and aunt under the rubble and since then has questioned the whole construction industry. “Of course, a building can be damaged, maybe even severely. But it shouldn’t have led to the death of so many people,” she says. Construction flaws, as well as serious errors in building supervision, contributed to the catastrophe.

Amnesty for illegal buildings

So far, only individuals and not government representatives have faced trial. The construction sector is the main support of the Turkish economy, and therefore, of President Erdogan as well. Observers say that over the years, this sector has grown uncontrollably.

Builders with close connections to the highest circles of politics: this is not uncommon. In addition, there is an uncontrolled proliferation of illegal constructions throughout the country, structurally promoted by the government through so-called building amnesties. These existed even before the Erdogan government. They retrospectively legalized illegally built houses or additional floors, often before elections in order to gain votes, most recently in 2018.

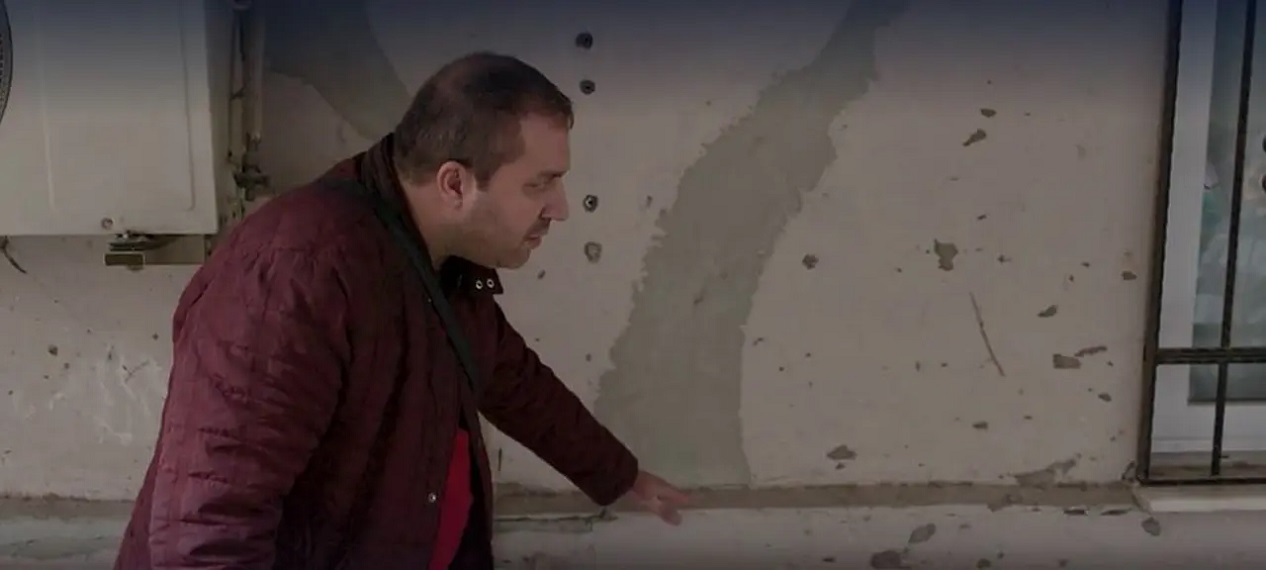

That is why the family of 9-year-old Bünyamin has mistrust towards the structural integrity of their apartment building on the outskirts of Iskenderun. Large cracks can be seen in the exterior walls since the earthquake, which were patched up with some cement.

Bünyamin’s father, Mustafa, stands in front of it, shaking his head. “All these cracks here, already covered up on the outside, can still be seen in our apartment. This crack here runs through the entire wall.” State assessors recently completed their report: the house is not damaged and therefore habitable.

A dilapidated apartment for sale

Some of the neighbors on the upper floors have moved back in as a result. However, Bünyamin and his family still cannot imagine doing so. The reasons become even clearer when entering the basement apartment: large cracks everywhere, some meters long. The extent to which load-bearing pillars have been damaged is unknown to the family, but distrust and trauma prevail. “Fear, just pure fear is what I feel here,” Bünyamin says softly, while tears well up in his parents’ eyes.

They had just finished paying off the three-room apartment shortly before the earthquake, and now they want to sell it. “I haven’t had anything renovated here,” Mustafa explains. “If I sell it to someone, I have to do it with a clear conscience. The person must have seen it all.”

Whether they can sell the apartment is questionable. But Mustafa believes there are enough people who would buy it, superficially renovate everything, and then rent it out.

The family wants to leave Iskenderun – the father is still looking for a job. They are reminded too much of the earthquake here, as well as the demolition work, says Bünyamin’s mother, Mehpare. “And the aftershocks seem to have no end, they won’t let us forget it all.”